Inter-nyet. How Putin wants to disconnect Russia from the global Internet

W skrócie

Russia is very efficient in cyber-offensive – but it doesn’t do so well in terms of defensive activities. For years now, it has been able to – unofficially – probe the resilience of IT systems, e.g. in Estonia. However, it has seriously surprised the western world with its ability to „mingle” in the elections in 2016. Meanwhile, the Internet has allowed free circulation of messages to grow within the country, where criticism of Vladimir Putin is possible. The regime is struggling to keep its eye on the ball and minimize and subordinate this independent space.

Vladimir Putin has put much effort into subduing television since he took power. The president claimed that it is the television, not the press or radio, that shapes public opinion. Therefore, full control over his image in this media sector has become a priority for him. It was thanks to his control over television that he was able to fish out antics from the bottom of the Black Sea during his recreational diving, work out at the home gym (even though he forgot to put the weights on the barbell), or showing off his judo skills by spreading his opponents on the mat.

The Kursk issue may speak volumes of this approach. When the submarine sank in 2000, a private TV station ORT, owned by the oligarch Boris Bierezowski, associated with Yeltsin, emitted a recording of a desperate mother of one of the sailors, accusing the then deputy prime minister of idleness and causing the death of sailors. Putin was not fond of the television’s critical opinion of him. Bierezowski – if one believes his recollections from the video below – was presented Putin’s decision, according to which he was to transfer 100% of the station’s shares to the state. The oligarch tried to defend himself, but the „Russian persuasion methods” made him succumb. He never learned who took over these shares. He left the country soon after.

Television has allowed Putin to control public opinion for years. However, at last, the Internet reached Russia as well. According to The Economist, the same number of Russians aged 18-44 watch movies on YouTube and the main state television channel (i.e. over 80%). Moreover, „news” is the fourth most popular category on Russian YouTube. Over a million users watch Alexei Navalny’s weekly live program on this website. The information program on the main state television channel attracts only three or four times more. Interviews conducted by another YouTuber, Yuriy Duda, in turn, are watched by about 10 million people on average.

According to the Levada Center, an independent opinion research centre, between April and September 2018, almost one in ten Russians ceased to draw news from television and started looking on the Internet. Already 37% of survey participants acquire information this way. The surveys results regarding trust for news sources are even more meaningful. Nearly half of respondents trust the information provided on TV, but ten years ago, this percentage used to be as high as 79%. Meanwhile, confidence in content found online increased from only 7% to 24%.

The Empire strikes back

The Russian president is a huge fan of technology – which would largely explain why – as the first on such a scale – he built competencies for the „armed” use of social networks during the elections in the US or France. Putin fights on three fronts in domestic politics: he wants to get details on what the Russians are doing online, allow punishment for spreading „unconfirmed information” and… disconnect the Russian Internet from the global one (or at least have such an option).

Let’s start with the first of these control tools. For instance, in recent years, Russia saw the emergence of two significant platforms – VKontakte, which is an alternative to Facebook, and Telegram, an app for encrypted communication. As you may have guessed, the possibility of intercepting data regarding citizens was very alluring to the Russian government. Putin began to exert pressure on the app’s developers, to – in a gesture of well-understood Russian hospitality – share the users’ data with the intelligence service.

The intelligence got to serious work in 2011, when protests broke out in the country, accusing Putin of falsifying the elections. The authorities of the Republic ordered Pavel Durov, the founder and president of VKontakte, to close the site temporarily. He refused. For two years, he tried to resist the pressure exerted on him by the services that demanded to share the data. In April 2013, the police searched Durov’s home – under extremely creative charges of driving over a traffic policeman’s foot.

The start-up entrepreneur decided to leave the country and vanished for some time. A few days after the search, the other two founders of the website sold their 48% shares to United Capital Partners, owned by Putin’s ally, Ilya Sherbovich. In January 2014, Durov sold the rest of his shares to the then richest man in Russia and the next close ally of Putin, Alisher Usmanov.

After leaving the country, Durov founded Telegram – an instant messenger allowing an exchange of encrypted messages (including online phone calls). In May 2018, the Russian state formally blocked access to the app. In spite of these attempts, Telegram is still extremely popular, and politicians, even those far from the opposition, use it as well.

The bad old censorship

However, Russians primarily make use of non-Russian sites – such as YouTube – and forcing these techno-giants to cooperate with the intelligence is much harder. Google itself acknowledges in a report on transparency that the most notices about removing links to pages from the search engine are received from the Russian government. In the first half of 2018 alone, it was over 19,000 notices – compared to 10 (in words: ten) from the Polish authorities, or 1002 from the US government. If you cannot acquire the data or remove content from a non-Russian site – you can always try to punish their creators.

It seems to be the real aim of the law adopted in mid-March by the Duma, allowing the prosecution of people propagating the – quite loosely defined – „unconfirmed information” on the Internet. The official goal of the new regulation is to prosecute fake news. Any hope that the Russian government would restrict itself to such activities is like counting on the guests coming to a house party to only help themselves to a single crisp.

A new form of the iron curtain

Finally, the last of the Internet control methods: allowing it to be cut off from foreign networks. In February this year, the news spread around the world that the Russians will try to experimentally cut themselves off from the rest of the Internet by April. The excuse is their preparations of the national National Digital Economy Program, as presented to the Duma in the preliminary version last year. It forces telecom companies – Internet providers – to prepare for a situation in which the Internet in Russia is isolated from the global network (on account of „sinister foreign powers”, of course, as always in this country’s history).

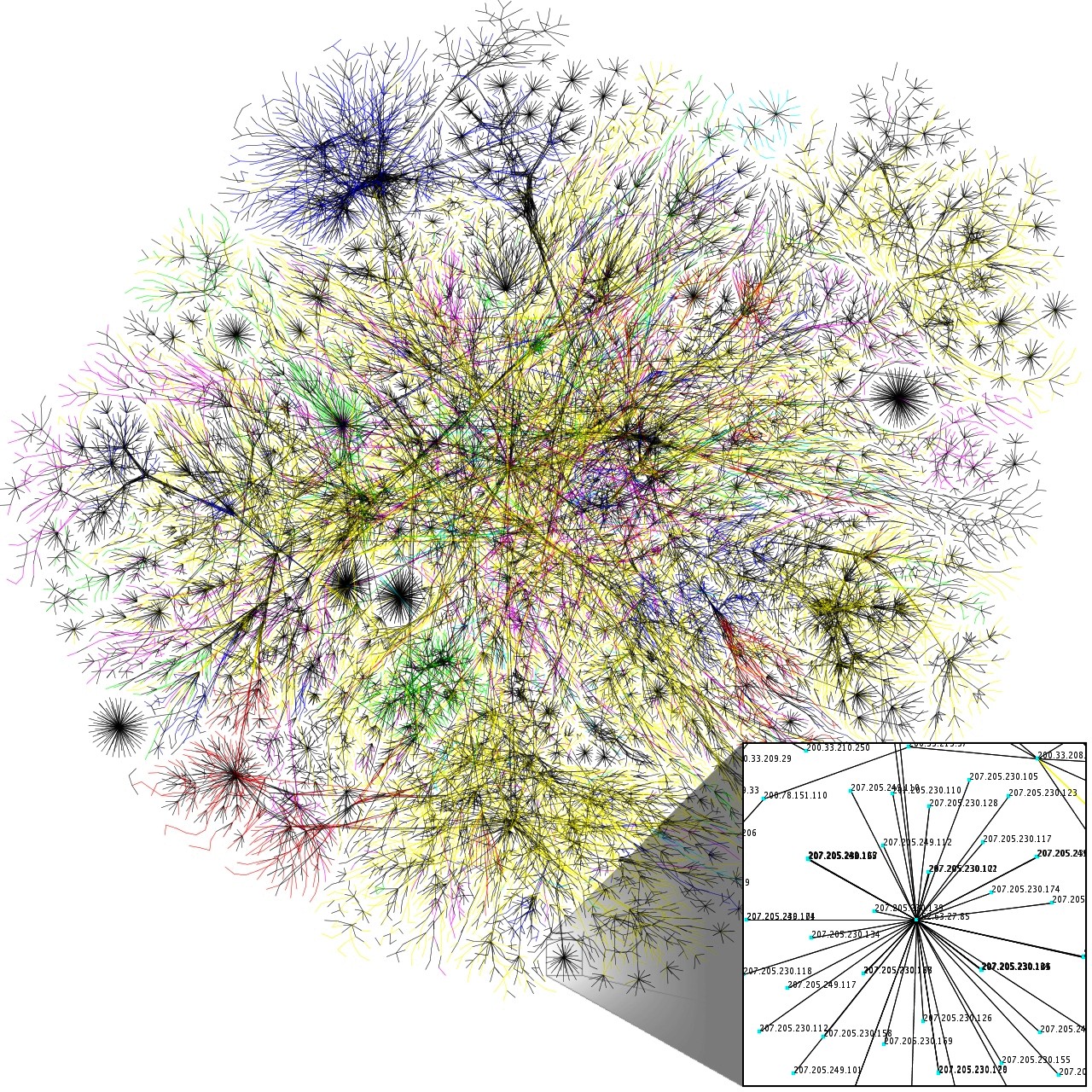

Therefore, Russia is building its equivalent of the „online address book”, or the Domain Name System (DNS). In practice, it is responsible for translating domain names (e.g. www.klubjagiellonski.pl – attention, self-promotion) to IP addresses that are understandable by computers and servers making up the network (in this case: 195.201.74.26). Currently, 12 organizations are responsible for maintaining the DNS system – none of them is based in Russia (though of course, there are many, many more copies of the „dictionary” itself). Interestingly, when asked a year ago about what he would have designed differently in the WWW – in the light of today’s knowledge – Tim Berners-Lee pointed to the DNS system, due to its centralisation.

Above all, however, the government wants all Internet traffic to pass through state-controlled and Russia-based routers. Currently, a packet sent from a phone or a computer in Russia – for example, containing a request to download the website www.klubjagiellonski.pl – may follow many paths, leaving the country in various „leaps” between nodes. The Russian government’s intention is for the traffic generated by the Russians to first pass through the network’s border nodes, located on Federation territory, or „gates” of sorts. In the event of issuing an appropriate order in such nodes, any packets directed „abroad” could be dropped there, and only those directed to Russian servers or computers would be forwarded. In an analogue world, this would seem rather plain and simple; after all, this is how state borders work, but the Internet cares little for real-world geography.

Is this plan going to succeed in Russia? In his statement for The Guardian Leonid Volkov, Navalny’s co-worker and IT expert stated that they had tried to do it in 2014, but to no avail. In February, news has spread around the media worldwide that before 1 April, Russians will try again – but the experiment has not happened so far. According to Volkov, they need five more years to have the chance to carry out such isolation.

What is President Putin playing for?

The possibility of disconnecting from the world is supposedly an answer (in the form of „cyber-counterattack” or „cyber-embargo”) to the threat of reaction to Russian cyberattacks and interference in elections in the democratic part of the world, as signalled by NATO several times.

Above all, it allows Putin to kill two birds with one stone. As a side gain, this creates a tool that will enable effective communication control in the event of internal disruptions – both cutting off the public from YouTube and similar websites, as well as, e.g. complicating the use of encrypted communication via Telegram.

„It can be clearly seen that the Internet, affected by international mistrust and geostrategic competition, broke up into Internets” – Grzegorz Lewicki wrote about the American, Russian and Chinese visions of the network in an article in the „Plus Minus” weekly. Will this Russian attempt at establishing their equivalent of the Chinese Great Firewall be successful? In contrast to the Middle Kingdom, the Federation is very late in creating (and closing) gates and fences to bar its part of the network. Above all, the Russian market is so small (not only on account of the number of citizens but primarily – of their wealth) that it seems impossible to repeat the Chinese way of shutdown in terms of western applications and platforms as well. Therefore, what remains is to lock away specific „critics” for their videos – and the common human fear, leading to self-censorship.

Polish version is available here.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2019" (below) is mentioned.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2019" (below) is mentioned.

The publication co-financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland as part of the public project "Public Diplomacy 2019" („Dyplomacja Publiczna 2019”). This publication reflects the views of the author and is not an official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.