The French public supports Ukraine. Is this the definite end of the partnership with Russia?

W skrócie

More insistence on the achieved security guarantees and less on the NATO invitation would have made the NATO summit in Vilnius a success in terms of public communication. It was clear in advance that the US did not want a commitment to an invitation to NATO. There is a real support for Ukraine among the French public, which led some politicians to change their discourse on Russia, at least tactically. Two main elements drive French foreign policy – fundamental principles of the international order and the need to preserve European unity. Marie Dumoulin, director of the Wider Europe programme at the ECFR, talks to Michal Wojtylo about the future of Western (incl. French) support for Ukraine.

Michal Wojtylo: What is the most and the least probable scenario for the war in Ukraine?

Marie Dumoulin: I guess the most probable is, unfortunately, a lengthy war with higher intensity and on a much wider front line than what we had seen between 2014 and 2022. The least feasible is probably Putin suddenly deciding to go to the negotiation table.

When you say lengthy conflict, what do you mean? 5 years or more like 20?

It is already a long war – there had been 8 years of conflict before the large-scale invasion. 5 years is realistic, but it can be more.

As Fredrik Löjdquist, director of the SCEEUS, said in a recent interview for Klub Jagiellonski: ‘The outcome of the war in Ukraine will depend very much on what the West is willing and able to do’. Not so long ago, there was a NATO summit in Vilnius. What can we say, looking at the discussions there and around it, about the future of Western military support for Ukraine?

First, we have to distinguish the NATO support from the Western one. The former has happened mostly outside of NATO, also to keep NATO outside of the conflict. This does not mean the NATO summit did not send important signals to the Ukrainian, European societies and to Russia.

For obvious and good reasons at the summit, the Ukrainians were pushing to get a political invitation to future membership in NATO. They did not get it which is what everyone – also in Moscow – noted as a sign of too weak support by the West. The message could have been stronger.

However, in reality, the fact that Ukraine did not receive an invitation does not mean that the Western support is weak. The most important part of the event was the declaration signed by several countries, including all G7 members, on security guarantees to Ukraine, which means there is a long-term commitment of Western countries to Ukraine’s security.

I am a bit afraid that the Ukrainian insistence on the NATO invitation made the issue too central and sort of weakened the message from the summit. More insistence on the security guarantees part would have made the summit a success in terms of public communication.

To sum it up, in terms of a communication strategy for the general public, you would say it would be probably better for Ukraine to focus less on its future NATO membership?

It was clear ahead of the Vilnius summit that the US did not want a commitment on an invitation to NATO. In a merely tactical way, given that, without the US on board, it was highly unlikely that something like that happens, I think the Ukrainians should have focused on what they could realistically get and what they actually got which is the security guarantees part.

Talking about Western support, I would also like to ask you about Ukraine’s perspectives on the EU accession. Recently, there has been a popular piece in Financial Times about ‘The “monumental consequences” of Ukraine joining the EU’ and that is kind of a symptom of a broader, recent talk among experts on the consequences of Ukraine’s EU accession, not only on Kyiv, but also on the EU itself. So what do you think are the main obstacles from the Western side to get Ukraine into the EU?

It is good that this discussion happens before integrating Ukraine because the whole issue is not only a political signal of support. It will have huge consequences for the EU itself, for example in terms of institutional setup. Ukraine is a big country with more than 40 million inhabitants. It means a certain number of members of Parliament, and a strong political weight in the Commission and the Council.

As for concrete issues, we must be aware that integrating Ukraine will not be easy because the country will be heavily destroyed by the war. And even before the war, Ukraine was a relatively poor country in comparison to other European countries with an insufficient quality of infrastructure and a huge agricultural sector. Basically, integrating Ukraine would mean that structural funds that are now benefiting a number of EU countries, including Poland, would be vastly reoriented towards Ukraine.

So these are issues that must be discussed beforehand in order to make sure that Ukraine can be integrated in the best possible way. Also, we have to keep in mind that Ukraine is not the only country that is supposed to be integrated and that ultimately the next wave of enlargements could include up to ten countries. That requires especially institutional reforms to make sure that the EU still can function after integrating such a considerable number of countries.

What do you think are the real or probable expectations of the Ukrainian government concerning its future in the EU? Officially we can hear a lot of ambitious plans from Kyiv but when you are at the negotiation table, you start the betting from the most beneficial proposals. Often the expected endgame is somewhere lower.

I was in Kyiv in early July and this is one of the issues that we discussed the most, both with government representatives and the civil society. My feeling is that there is a very strong push by the government to get things done as soon as possible and they also do their homework in that. There are the seven recommendations that had been formulated when Ukraine was given candidate status and most of these recommendations are being implemented. There still are some issues which require work, but this gives the impression that the government wants to make sure that it has the best possible case at the end of this year when the decision on opening the negotiations will be made.

As you said, there have been official statements mentioning an EU accession within a very short time, which is not realistic. I think the Ukrainian government knows it, but that is part of the push to get things done quickly.

On the part of the civil society, the message was a bit different. What they told us was that they quickly need a strong commitment to Ukraine’s security, also from NATO. However, they talked about the EU accession process as something that needed to be done well and so it needed time. They said it is the best leverage that they have to make sure that the fight against corruption, institution building, and justice reform are being done properly and implemented sustainably.

Other than Western support the important factor contributing to the result of the war is the internal dynamics in Russia. A couple of weeks ago, there was the case of Prigozhin’s affair, called by many mutiny. What was it and what could be our conclusions taken from the whole affair about the state of the internal situation in Russia?

I still struggle to understand what it was and what it is supposed to mean for the future. I guess mutiny is a good description because it is quite a neutral term – people in arms rebelling against orders. I still do not know what the intention of Prigozhin was when he started his march on Moscow. What he said is that he just wanted to get rid of Shoigu and Gerasimov and there was no questioning of the authority of the Supreme Commander. The whole affair is very difficult to make sense of it. Especially the way it ended with some sort of compromise. We do not know by whom it was negotiated and we do not know its terms.

The first lesson from the event is that there is a certain level of dissatisfaction in some parts of the armed forces with the way the war is conducted. Prigozhin was just a manifestation of this emotion – I do not think it is limited to the Wagner Group. The fact that they could take the military buildings in Rostov without encountering real resistance means there was some level of sympathy towards the mutiny in the armed forces. Although in the case of Wagner, what triggered the events was also the fear that Prigozhin would be deprived of his assets.

The second lesson is the fact that in some instances Putin can accept to go for a compromise. Again, I do not know what are its terms and how long it will last – whether Prigozhin will not fall out of a window at some point. But for now, he engaged in putting pressure on the regime and was not crushed either. It probably reveals some weaknesses of the Russian state that will not disappear overnight.

Let’s go into a French perspective on the Ukraine conflict. How would you describe the changes in it since February last year? Do you see any shifts in Russia policy among society and in the domestic political arena? Does the support for Ukraine start to fade in France?

There was very little knowledge about Ukraine before February 2022 among French society. All of a sudden people discovered this country and there was a huge level of sympathy for Ukraine. It is lasting – in a recent Eurobarometer poll levels of support in the French public were similar to the ones in the Baltic States. This is consistent with other polls, such as the ones conducted by ECFR.

The war is less present in the media than it was in the first months of the war, but it is still there and it is still not very far from the top news. Even during the presidential election in France, the campaigning was often marginalised by the war. That leads me to the second point about the perspective of the political elite.

In the French political parties – especially on the far-right and the far-left – there used to be a lot of people who had sympathies for Russia. I guess these people are still there but you do not hear them that much anymore and a number of them have changed their views. It was very clear during the presidential campaign last year – even Marine Le Pen had to change her discourse regarding Russia to help her campaign. I think this is one of the factors that made a difference in her race with the other far-right candidate, Eric Zemmour. It is probably not the only factor but the simple fact that she felt she had to change her discourse means that in France the public support for Ukraine has a very concrete political translation.

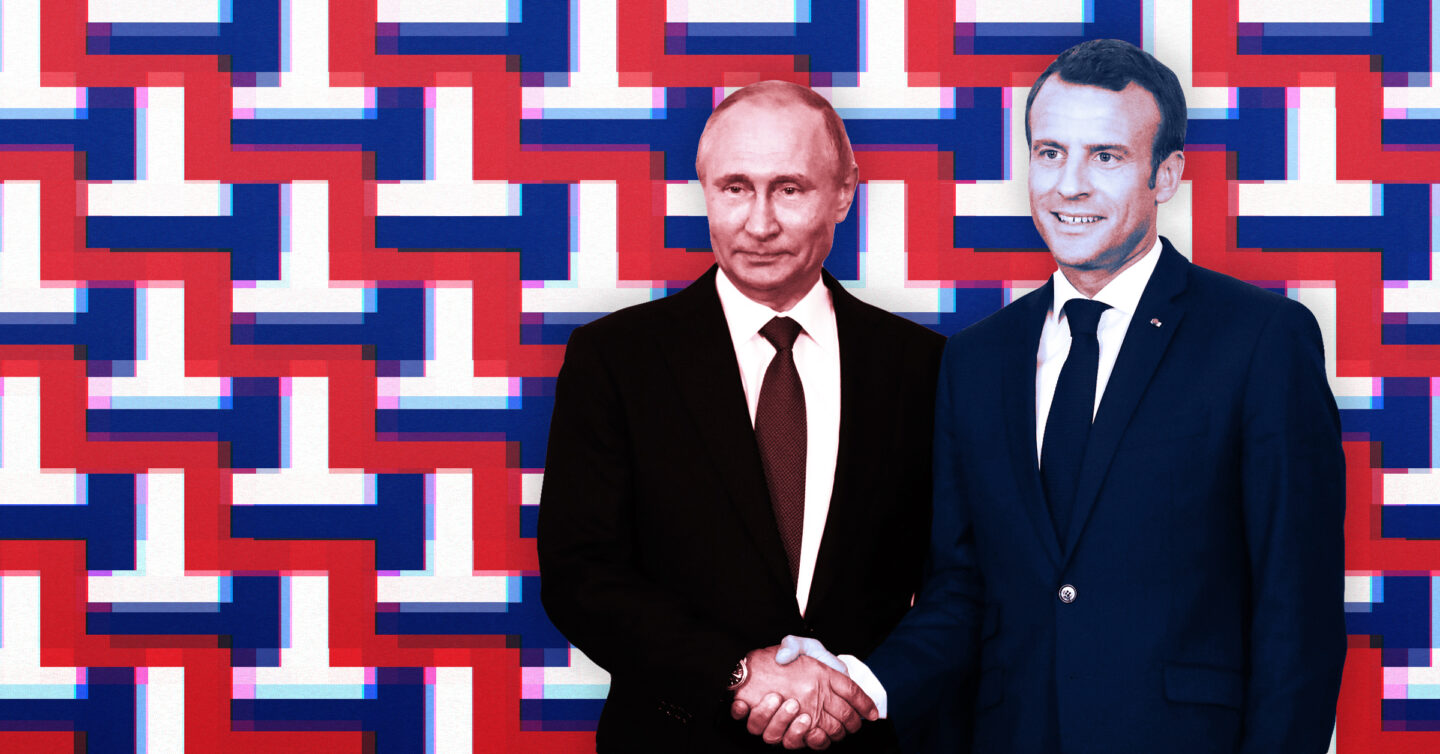

In Poland, since the start of the war, there was a kind of confusion about the French approach to the Russian aggression. On the one side, the French were spearheading the military support for Ukraine. But on the other side, there was always the question of the French companies still staying in Russia and Emmanuel Macron calling Vladimir Putin. How would you explain the adverse actions of different French actors if there is such huge public support for Ukraine?

We have to distinguish clearly between business and French foreign policy. French business was before February 2022 one of the biggest, if not the biggest foreign direct investor in Russia. Also, it was the first foreign employer because French business there was mostly big companies, especially in the retail sector – e.g. Leroy Merlin and Auchan.

French companies made diverse decisions. Some decided to leave very early. For example, Renault had made huge investments in Russia and just overnight sold it for a small fraction of its value. Other businesses did not make the same decision which had consequences for their image. What is more, recently we have seen that Danone, which had stayed in Russia, has been deprived of its assets by the Russian state.

These are private corporate decisions. They calculate the risks and the benefits and ultimately it is their money. Unless there are sanctions on a specific area, the government cannot forbid them to stay in another country.

When it comes to French foreign policy, for me it is much more consistent than the way it is perceived, especially in Central and Eastern Europe. There are two main elements that drive French policy. The first one is the defence of fundamental principles of the international order. The response to the Russian aggression is not only about Ukraine it is also about territorial integrity, the equal sovereignty of states. We need to make the case for these principles because if they are not there, we are doomed.

The second (less obvious) principle is the need to preserve European unity. There was a lot of criticism towards Macron because he is always seen as doing things on his own in foreign policy. However, France is keen to keep European unity – when the war started France had the EU presidency and was a sort of driver to bring all the 27 EU member states together quickly and make the strong common decisions that the EU has made back then.

The strong commitment of France to support Ukraine is not contradictory to the fact that Macron has tried to keep an engagement with Putin, at least in the first months of the war. They had frequent contact until Russian atrocities in Bucha and Irpin were discovered. After that, I think that Macron realized that he is talking to someone who ordered war crimes.

Until then, I guess Macron’s idea was that someone has to keep talking to Putin and to convey him our messages and that he had a relationship with Putin that allowed him to do it. After Bucha and Irpin things became more difficult and it made less sense to have frequent dialogue.

There still are issues on which I think he would continue to talk to Putin, like the nuclear power plant of Zaporizhzhia and the grain deal – calls on managing the consequences of the war but not hoping to bring Putin back to the negotiation table.

Last question – in recent years there was a lot of talk about Macron’s idea of European strategic autonomy. How do you think this concept has changed since the start of the war? Is it still present in the French narrative? Does the war in Ukraine and everything that has happened around it make the case for strategic autonomy?

The French officials recently have not been using the term strategic autonomy so frequently. Even before the war in Ukraine, they were shifting to something like European strategic sovereignty which more or less has the same in meaning, i.e. Europeans being able to deal with their own strategic challenges and security issues.

Its aim is not to question the alliance with the United States and the transatlantic link. It basically means that we do not know where the US is heading and whether we will always be able to rely on the US to ensure security in Europe. By the way, Washington is also asking us to do more.

This discussion has also very concrete consequences – at least in the way the French see it– meaning that Europeans should also be able to produce what they need for their own security, including military equipments.

There are still discussions on what the French propose and whether they are right. But the fact is that the EU is moving towards more strategic sovereignty. Because of the war in Ukraine, we have achieved huge steps in being able to deal with security issues in an EU framework, which was not so much the case before. Of course, there still are areas where the progress is lagging behind and this will have long term consequences.

This is mostly the case in the defence industrial sector where we should be able to step up production much faster to support Ukraine, but also to ensure fulfilling our own needs. Because of the urgency of the situation, we use resources to buy things from shelves outside of Europe. It is money you spend now, but with a very long lifespan for the equipment that will tie you to the provider and not contribute to building your own production. The biggest frustration the French have is that they see a lot of EU countries now taking defence more seriously and increasing their investment in defence but without contributing to building a more powerful defence industry in Europe.

Polish version of the interview is available here.

Marie Dumoulin – the director of the Wider Europe programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations. Prior to joining ECFR, Dumoulin worked as a French career diplomat, worked with the policy planning staff (CAPS) and headed the Russia and Eastern Europe Department of the French Foreign Ministry. Dumoulin holds a PhD from the Paris Institute for Political Science (Sciences Po).

Public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2023".

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the official positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.”

Marie Dumoulin

Michał Wojtyło