Are we in for a chip world war? The semiconductor industry on the verge of its limits

W skrócie

Ice-covered Texas, Japanese factory fire, Taiwan’s worst drought in decades, COVID-19 pandemic, Trump’s tech war. What do these events have in common? All of them have contributed to some degree to the global crisis in the semiconductor market.

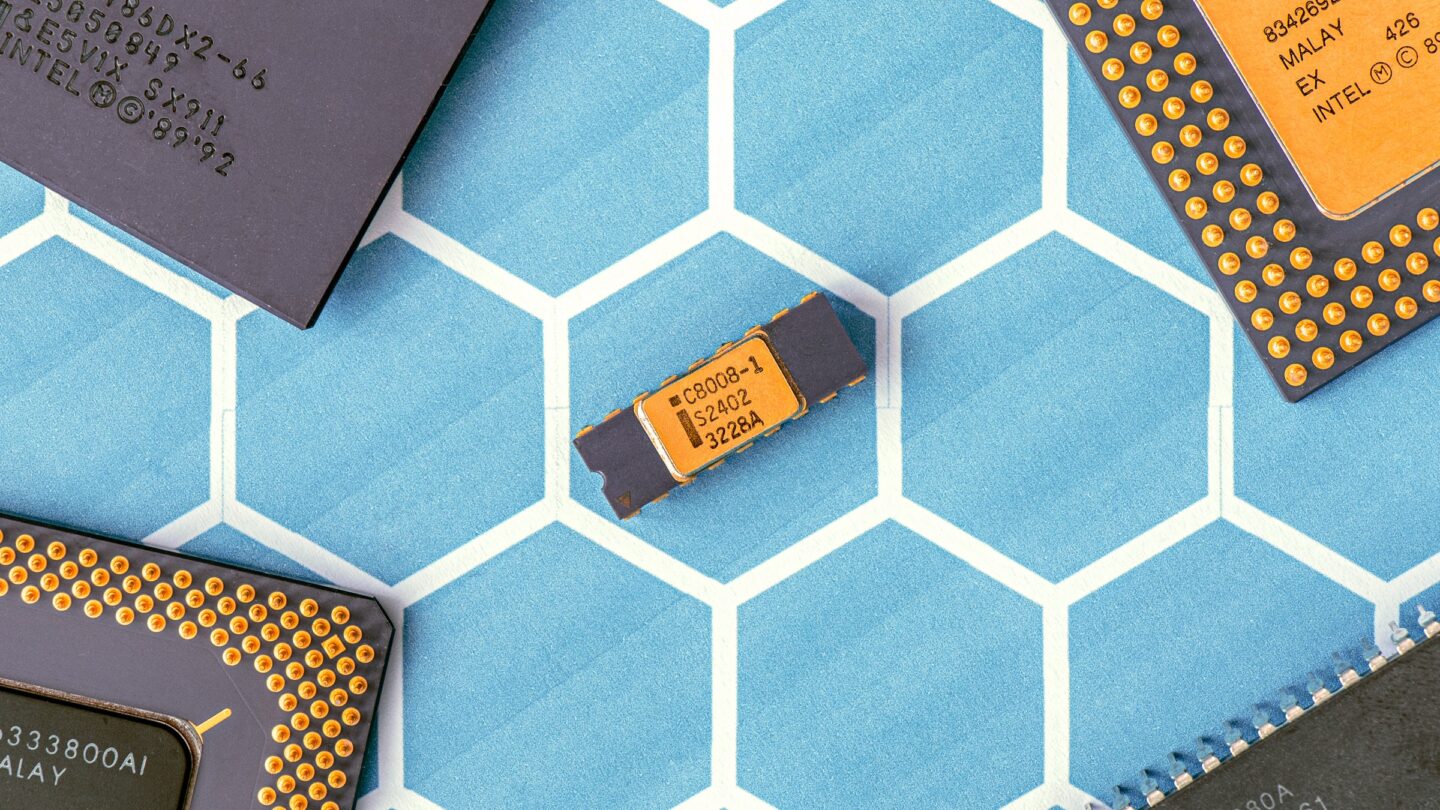

Chips at the centre of our lives

Semiconductors, or so-called chips, are a key element in a whole range of devices, such as smartphones, cars and military equipment. As the digital revolution advances, their importance will continue to grow rapidly.

Chips have become a strategic resource for economic stability. Streaming services and data centers are constantly springing up. Self-driving vehicle tests are underway, and Jeff Bezos has announced that he would go to space. This is a taste of changes waiting just around the corner.

But what happens when microelectronics run out? We are dealing with such a situation right now, and there are at least several reasons for it.

Hidden chaos

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, the rapid pace of global digitisation had put pressure on supply chains in the semiconductor sector. The production of integrated circuits requires enormous investment outlays and specialised engineering knowledge. Building a modern factory takes several years and costs billions of dollars. The high-pace industry was completely disrupted by weather, a trade war and the outbreak of the pandemic.

In February, an extreme winter disrupted many companies in Texas, where Samsung Electronics manufactures 28% of its chips, and Infineon and NXP make car components. A Renesas factory – an important supplier for the automotive market – burned down in Japan. Taiwan, a key location on the semiconductor map, was hit by the worst drought in several decades, which resulted in minor power cuts and uncertainty about whether the continuity of water supply would be maintained (and the industry needs this raw material). Taipei is also battling another COVID wave, more severe than previous ones.

Lockdowns and severe government restrictions have turned the lives of millions of people upside down. They have led to massive disruptions in demand and a boom in remote work and e-commerce. Locked up in their homes, people began to place countless orders for IT and household equipment. Electronics manufacturers swiftly increased their chip orders to keep up with market needs.

Some, such as Huawei, have stockpiled. As part of the technological feud between the US and the PRC, the Trump administration has prevented some Chinese companies from sourcing modern integrated circuits. Before the restrictions went into effect, commercially blacklisted companies (and not only those; there were concerns in China about the possibility of the list expanding) purchased additional quantities of microelectronics to continue production without interruption. Despite the above, it is estimated that due to sanctions, Huawei will make around 60% fewer smartphones this year than last year.

The automotive market has also been hit by the pandemic. The first months of 2020 brought a drastic decline in demand. Anticipating that this state of affairs would continue for some time, manufacturers limited their components’ purchases. The second half of the year brought an unexpected change – the cars began to sell.

The method of acquiring parts turned out to be a trap. The just-in-time system is based on stocking on a regular basis, without storing large reserves of parts. Until now, many car manufacturers have procured semiconductors through intermediaries but have not been treating them as critical components. Consequently, the automotive industry has not developed special relationships with their manufacturers. So when there were large fluctuations between demand and supply, the latter were unable to react adequately. According to forecasts, the situation may hold until 2022 or longer.

Losses go into hundreds of billions of dollars

Due to the lack of chips, enterprises are unable to fully respond to the increased demand. Both smaller and larger players lower their profit forecasts and shut down production lines. Many have been affected. According to Goldman Sachs, as many as 169 industries will suffer to varying degrees, from manufacturers of consumer electronics and air conditioning systems to breweries and soap factories.

Nissan will make 0.5 million fewer cars this year. Ford’s losses will amount to $2.5 billion, and General Motors will lose $2 billion. The entire global automotive industry will lose approximately $110 billion in 2021. Apple, with its leverage and expertise in managing a complex supply chain, also experienced shortages – it postponed the manufacture of some MacBooks and iPads. Sony is unable to supply the right amount of PlayStation 5 consoles. Uncertainty has engulfed the military circles and defence companies, as supply interruptions threaten to disrupt the schedule for the creation of key systems and weapons.

The affected companies are desperately trying to cut costs. They are liaising directly with microelectronics manufacturers and appealing to governments for help. In Taiwan, delegations at the intersection of business and politics have recently started to become apparent.

Giants fighting in the background

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – the world’s largest manufacturer of custom integrated circuits – operates on the island, which Beijing treats as a rebel province. There are three models of running a chip business. Companies design and fabless chips, run foundries and make-to-order (pure-play foundries), or handle everything – from design through manufacturing to testing (IDM). TSMC is a pure-play company whose services are used by, for example, Apple, Google, Nvidia, Qualcomm, Nintendo and the Pentagon. In 2019, it made almost 11 thousand types of products for 499 customers.

Its strategy was adapted to the economic boom of the globalisation era when the manufacturing process was dispersed in such a way as to maximise profits. Fabless manufacturers cut costs by focusing solely on projects, and TSMC achieves economies of scale and momentum when fulfilling orders for them, which allows gaining priority, for example, during the purchasing of the necessary machines. A large part of the profits is reinvested in R&D, and the process experience gained along the way bears fruit in the development of innovative engineering solutions.

The company enjoys great prestige and is sometimes called the company that built Taiwan. This year, its capital expenditure is expected to be the equivalent of 20% of private sector investment on the island, and TSMC plans a global expansion worth $100 billion within three years (2021–23).

The Korean Samsung has also announced the construction of a factory in the USA. In the 1990s, 20 companies in the world had the capacity to make advanced chips. Today, the latest technologies are only used by TSMC and Samsung (IDM, which introduced the foundry segment in 2005).

Kim Ki-nam, Samsung’s vice president, believes that long-term strategies should be drawn up because the entire sector is facing a turning point. South Korean chip manufacturers plan to invest around $450 billion by 2030. All with the support of the government, which will provide tax breaks and the necessary support to make the Republic of Korea a chip powerhouse.

Countries that manufacture semiconductors and have the ambition to lead the digital revolution recognise the importance of today’s issues and the value of resilient supply chains. Japan’s former Minister of Economic Policy, Akira Amari, bluntly stated that „those who control semiconductors will control the world.”

Amari is part of a task force set up in Tokyo to address the security of supply and competitiveness issues of Japanese chip companies. In the 1980s, the Land of the Rising Sun was one of the industry leaders, but it has lost its edge over the years.

Increasing rivalry with China and national security issues prompted President Biden’s administration to federally support the US chip industry. First and foremost, it is about getting the production process back onto American soil. US companies lead the way in IC design, but a significant part of production takes place in Asia – for example, components for the F-35 fighters are made by TSMC.

This raises legitimate concerns in Washington, and the issues are being raised by politicians from both parties. Joe Biden plans to spend $50 billion on building new factories and advancing semiconductor technology research as part of his infrastructure redevelopment plan. The American government is encouraging companies from allied countries to invest in the United States. TSMC has already started building a factory worth $12 billion in Phoenix.

The native Intel (IDM) has also stepped into action, although it is facing a number of challenges. The company has been providing pioneering microelectronics solutions for many years, but it currently has a long backlog of rivals. And although it has announced capital expenditures of $20 billion for two factories in Arizona, it will be outsourcing the manufacture of about 1/5 of processors to TSMC in 2023.

China is facing even greater challenges, as it aims to set global standards in areas such as next-generation transmission networks, robotics, artificial intelligence or driving automation. So far, there has been a huge dependence of Chinese manufacturers on machinery and components made in the USA. However, the most advanced process hub of the leading Chinese manufacturer – Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) – is far ahead of the competition. In addition, the company has been subject to US sanctions.

Beijing is mobilising and spending billions of dollars on R&D and detailed studies of every part of its supply chains to overcome the current weakness and create the most independent industry possible.

Founded in 2016, Yangtze Memory Technologies Corp (YMTC) is researching where all the necessary materials come from, the way they travel before they are transformed into a finished product, and whether alternative sourcing mechanisms can be developed. However, the implementation of such a breakneck task, which is the transition to the next generation of chips, may take even dozen-odd years or more.

Not everyone can make semiconductors

„We are currently at 22 nm. Going from 22 to 2 nm is like jumping to the top of Taipei 101 – if you fail, you’ll crash.” This is how one of the European representatives of the industry commented on the plans of the European Union to obtain the most innovative manufacturing technology. The problem is that there are no tech giants in Europe who are consumers of these breakthroughs. Companies in the EU manufacture components for cars and equipment that do not use such sophisticated chips. Building a state-of-the-art manufacturing base to export to Asia and the US, with powerful competitors active in these parts, is unlikely to be profitable. The Community’s plans assume gaining a 20% share in the global market.

Western Digital’s CEO and TSMC’s CEO are sceptical about hard decoupling and building multiple production hubs around the world. Supply chains are tailored to be profitable and efficient. Trying to create a new system is economically unfeasible.

***

Some people have a problem with buying a console, others are worried about billions in losses, while others still are struggling to gain a safe advantage over their rivals. The report National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence states that, in order to secure its prosperity and security, the United States should maintain a 2-generation advantage over companies from the PRC in microelectronics.

Although Beijing will face many obstacles on its way to building a national chip arsenal, we are talking about huge investments, far-reaching plans and needs defined by decision-makers in terms of national security. On the other hand, Americans, Taiwanese, Japanese, Koreans and Europeans are just as serious about it. The inconspicuous chip has found its way to the centre of global competition.

Polish version is available here. Public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2021”. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the official positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2021" (below) is mentioned.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2021" (below) is mentioned.