Ban on the sale of combustion vehicles and a protectionist carbon tax. “Fit for 55”, the most ambitious climate plan in the history of the EU

W skrócie

A ban on the sale of combustion vehicles from 2035, border carbon tax for imports from outside the EU, increasing the target of RES share in energy production up to 40% and decarbonisation of buildings – these are just some of the plethora of suggestions put forward yesterday by the European Commission under the anticipated climate offensive. Dozen-odd pro-environmental projects point to one thing: the righteous dream of zero emission will require many sacrifices from all of us. A substantial debate is necessary also (and perhaps above all) in Poland, since Poland’s path to decarbonisation is the most demanding. Fit for 55 is the last call to make green and socially sustainable transformation topic number one in Poland.

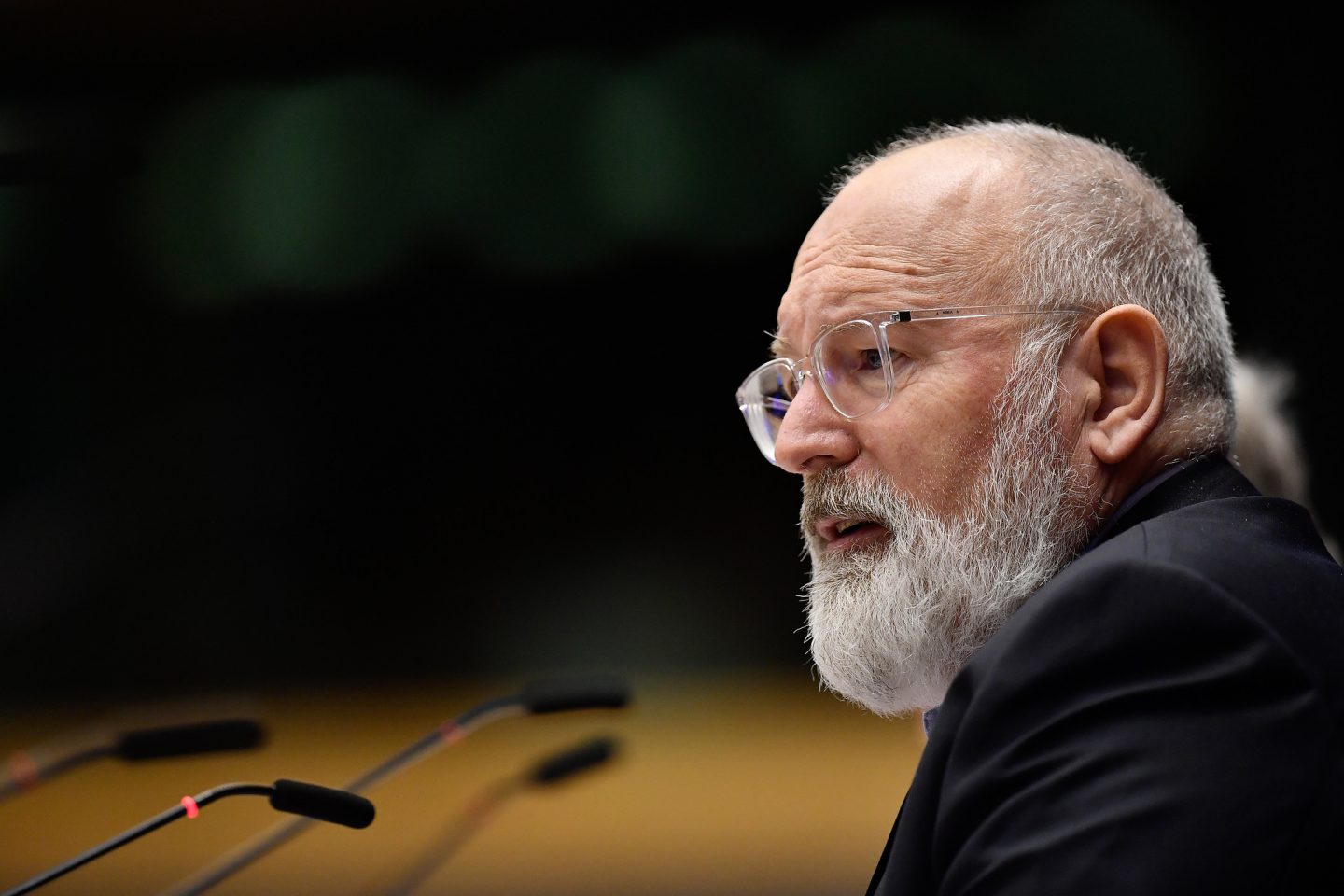

“Is Frans Timmermans bold or mad?” – this is how the POLITICO, friendly to the European mainstream, begins its text heralding the new initiative of the European Commission, Fit for 55. At yesterday’s press conference, apart from the Dutch vice-chairman responsible for the implementation of the European Green Deal, the new law proposals were presented by six commissioners.

All this shows us how controversial and broad-spanning the package of over a dozen EC projects is, aiming at changing the European economy forever, and thus the everyday life we all lead. Fit for 55 is a proposal of the most ambitious climate plan in the history of the European community. However, the presented package has so far been only a reference point in the initial negotiations, where particularly the poorer countries – including Poland – should fight tooth and nail for their specific conditions and lower development level to be taken into account.

During the next 2–3 years, no other topic will probably be as important on the EU forum, and public debate in Poland should reflect that. A serious discussion on this subject should start without any delay. So what is this mysterious EU package, and what does it include?

Do you want to accelerate the reduction of emissions by 2030? Brussels says “check”

Yesterday, the European Commission published a package of proposals under the Fit for 55 initiative, which aims to ensure that the EU is ready for the recently adopted tightening of CO2 emission reduction targets to at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels).

According to last year’s EC communiqué, the existing regulations would only allow reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 60% by 2050, hence the need for more restrictive milestones and the introduction of new tools. Although those saying that these proposals are exceptionally ambitious are right, it is worth remembering that this was also the case with the 55% target, which many of us simply did not notice at the time, not realising just how radical in practice these changes would need to be.

The package includes a tightening of the existing regulations:

- the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), including the Aviation and Maritime Transport Directive;

- regulations on the inclusion of greenhouse gas emissions and removals from activities related to land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF);

- effort sharing regulation (ESR);

- RES directive (RED);

- EnergyEfficiency Directives (EED);

- directive on alternative fuels infrastructure;

- CO2 emission standards for new cars;

- directive on the taxation of energy products and electricity.

New proposals were also introduced to the debate:

- ReFuelEU Aviation;

- FuelEU Maritime;

- Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism;

- Social Climate Fund;

- A new EU strategy for forestry.

Among all these guidelines, it is worth highlighting two proposals that raise the greatest controversy.

Radical decarbonisation of buildings and road transport

One of the highlights of the package is the reform of the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Under this EU system, there is a limit on greenhouse gas emission allowances for specific systems, which is decreasing year by year, leading to a gradual decarbonisation of Europe. So far, the energy sector, industry and flights within the EU have been included in the system. Companies that decarbonise faster, and thus do not use the allowances allocated to them, can resell them, which is intended to encourage their green transformation.

However, the existing provisions must be updated for the new 55% target. The European Commission wants to do this, among others, through a faster reduction of the allowance limit (by increasing the linear reduction factor) and by including new sectors into the system. Sea transport and aviation are to be added to the ETS. However, from the Polish perspective, the provision of an analogous, separate ETS system from 2025 (which is to be fully operational from 2026) for buildings and road transport is much more controversial. The European Commission argues that these particular sectors have not shown any significant progress in decarbonisation so far, despite the fact that they account for a significant share of the EU economy’s emissions.

Critics of this proposal emphasise that the additional burden related to the changes will fall on consumers, including the poorest, who are already in the group of energy-poor households (over 34 million people in the EU) or those socially excluded from transport.

Experts of the Polish Economic Institute (PIE) in this year’s report, Impact on Households of the Inclusion of Transport and Residential Buildings in the EU ETS, emphasise that such a solution (without aid tools) would mean an average increase in energy expenditure in the EU for 20% of the poorest households by around 50% (in Poland by 108% on average) and by 44% for transport. The authors indicate that the additional costs for EU households in this regard will amount to EUR 1.11 trillion in 2025–2040.

This proposal was openly criticised not only by the Polish government but also by the French MEP of the liberal group Renew Europe, Pascal Canfin, who recalled the riots from two years ago caused by the yellow vest movement (gilet jaunes) in France, which broke out after the announcement of energy price increases.

During his June speech in the European Parliament, he described the proposal as „politically and climatically suicidal” and one which strengthens the argument that EU’s green transformation should be paid for by increasing energy bills of all citizens (including the poorest ones), which will further antagonise people against the European Green Deal.

One must admit, however, that the European Commission notices the problem of excluding the poorer – at least in its narrative – and tries to mitigate the negative effects of these changes. As much as 25% of the new revenues from this system are to go directly to Brussels to be „poured” into the newly created Social Climate Fund for poor households, micro-enterprises and transport users.

During 2025–2032, the fund is to pay EUR 72.2 billion for the needs of those most affected by the changes. The money is to be granted to member states under specific projects (including those related to increasing the energy efficiency of buildings, clean heating and low-emission transport) according to a similar mechanism that was used at the EU Reconstruction Fund, which we described in our report recently. This is a significant change because, so far, the money from the ETS went directly to the Member States, which organised the auctions of emission permits. Now one-quarter of the new income sources will go to Brussels, which will distribute them according to its own criteria.

In order to decarbonise road transport, the European Commission is also proposing a drastic reduction of the current CO2 emission standards for new cars and vans. By 2030, emissions from this source are to drop by 55% (previously, this ratio was 37.5%), and in 2035 all new cars sold in the European Union are to be completely emission-free. The middle of the next decade has been chosen because of the average 15-year car lifespan in the EU – the goal for 2050 is for almost all combustion-engine passenger vehicles to leave European roads.

The proposal sparked a wave of harsh comments – there are fears that this change would deepen transport exclusion, particularly in less developed EU countries. The European Automobile Manufacturers Association (AUTA) also warns against overly ambitious goals that will further deepen the huge disproportions in the development of this sector between countries inside the EU – almost three-quarters of electric chargers for cars are found in only three countries (Netherlands – 66.7 thousand; Germany and France – approx. 45 thousand each). For comparison, Romania has only 493 such units.

Introduction of an effective border carbon tax

Fit for 55 also includes the idea of introducing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which is to ensure that, in the face of more and more expensive emission permits inside the EU, European companies will still be able to compete on the EU market with imports from third countries with no hard climate targets and where production is carried out with lowered environmental standards and therefore, at lower costs.

The new fee is to prevent the phenomenon of manufacture relocation outside the EU, where these standards are lower (carbon leakage). Such a situation would not only be detrimental due to the potential transfer of factories outside the EU, and thus the economic losses associated with it (including job losses), but also goods would then be made in countries with lower environmental standards, out of European countries’ control, which would also do little to help the climate.

The new tax is to be introduced from 2023 and fully applicable from 2026. It will apply to the production of iron, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, cement and electricity. Importers of these goods from outside the EU (except Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) will have to buy certificates, whose price corresponds to intra-EU CO2 emission prices, minus the carbon tax paid in their home country, as well as an amount corresponding to free allowances in the EU emissions trading system (whose pool would be reduced simultaneously).

This way, the EC wants to ensure the compliance of the entire process with the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), so that the new fee does not introduce double privileges for European companies – the EU industry cannot be simultaneously protected by a new tax for external entrepreneurs and free CO2 emission permits.

All revenues from the new tax (approx. EUR 10 billion a year, once fully enforced) will go to the EU coffers. The European Commission highlights that the new funds will help pay off the debt incurred by the EU to finance the Reconstruction Fund. It should be emphasised, however, that this is only a drop in the ocean of needs – the entire pool of the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility is as much as EUR 672.5 billion, which is to be repaid in 2028–2058.

The announcement of the tax itself triggered strong responses, especially in countries closely associated with the EU. PRC President Xi Jinping slated the initiative, stating that fighting climate change should not be an excuse to hit other countries with trade barriers. Representatives of Turkey and Russia also expressed their objections. There is also serious concern about the consequences for developing countries, which will be particularly sensitive to the effects of the new mechanism due to a lack of capital necessary to invest in low-carbon technologies.

Concern has also been voiced by the EU’s close allies. Roman Andarak, the head of Ukraine’s mission to the EU, emphasised that this issue would define EU-Ukrainian relations more than the humanitarian and technical aid provided to date. The EU is Ukraine’s main trading partner, and Kyiv estimates the losses related to the introduction of the border carbon tax at up to EUR 4 billion yearly. Earlier, John Kerry, the US President’s special envoy for climate issues, highlighted that the new tax should be a last resort.

The Eurocrats’ ambitious plans are one thing; their social acceptance is another

Fit for 55 and the tensions around it clearly show how closely the EU’s climate policy is connected to its foreign policy. Brussels aims to lead the world towards climate neutrality. The new tools are aimed at increasing the attractiveness of low-emission and zero-emission technologies by accelerating the unprofitability of using fossil fuels and creating an outlet for the economies manufacturing them. That is an optimistic scenario that does not necessarily have to come true.

The success of the entire plan depends on whether the EU will manage to maintain its economic competitiveness and whether the world’s most important countries follow the path of decarbonisation set by Brussels in their actual activities (and not only in PR announcements). As Donald Trump showed when he left the Paris Agreement, even the wealthy United States may deviate from this path after the next elections.

Of course, the proposals described above are merely a fraction of all the provisions in the EU Fit for 55 package and much more will be published. However, it is worth noting that the European debate is slowly moving away from generic slogans to the stage of specific proposals, which gives a tangible aspect to the so-far highly ideological discussion on mere numbers.

We are getting closer to accepting the key proposal in the European establishment – the green transformation will be costly and painful for everyone, especially the poorest. Europe must therefore make substantive and narrative preparations, also by creating instruments that minimise the negative effects of changes for those most exposed. Or perhaps even take a step back in some respects and make some of its goals more realistic? Without a pinch of political realism, we may face strong social opposition to ambitious climate assumptions.

Polish version is available here.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2021" (below) is mentioned.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2021" (below) is mentioned.

Public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the grant competition “Public Diplomacy 2021”. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the official positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.