Poland or the Netherlands? Who has gained more from Polish entry into the EU?

W skrócie

At the (corona)summit, the so-called Frugal Four (Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark) strongly demanded financial discipline and clear control over the rules for spending additional funds. These countries presented themselves as being strongly negatively affected by the wide-nation composition of the EU. Although this subject is often overlooked in the aggressive speeches of Western European representatives, the countries that have benefited the most from the European integration in the 21st century – also the broadest 2004 European integration in which Poland took part – were… in fact the members of the ‘Frugal Four’. Therefore, experts started debating the question: Who has benefited more from Polish entry into the EU? Us (Central and Eastern Europe) or them (the countries of the 'old Union’)?

Who won?

The European Commission practically upheld the total amount of Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) budget after 2020 (proposed back in 2018), i.e. nearly 1.1 trillion euro. From the very beginning, the EP has criticised the MFF cuts for 2021-27. It did not change its mind even after the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) was added to the joint account, with the result that the total EU budget would amount to EUR 1.82 trillion by 2027. And although it is more than 5% of the EU-27’s GDP, the demands of the North of Europe have been heard and ultimately obtaining these funds may be more difficult than before.

The ‘Frugal Four’ have succeeded in their negotiation. These countries have also seen their contributions reduced by a total of more than EUR 7.6 billion (approx. 10%). Over time, Finland has also joined the club, and Germany has followed suit, ready to do a lot just to maintain the cohesion of the EU on which they have built their position over the last decades.

The resulting gap in the budget will now also have to be filled by the other countries, according to their gross national income. What is more, it was the countries of the ‘Frugal Four’ that imposed stricter rules on the distribution and management of the new fund on others. The leaders who paid particular attention at the summit to the rules of spending funds, with their diplomatic and negotiating activities show how far they are from complying with the laws governing the MFF mechanism.

Deepening integration without solidarity

The rebates on the budgetary contribution for net contributors show that the communitarisation of debt, which would be evidence of deepening integration, does not necessarily go hand in hand with the principle of solidarity. And it is what guides cohesion policy (the largest part of the MFF), the one aimed at equalizing the costs associated with opening the markets of weaker economies. The decision to reduce contributions not only reveals a deviation from the principle of solidarity. It also shows that a common-sense cost-benefit account seems alien to the richest EU countries.

Reducing the contributions of the ‘Frugal Four’ to the EU is, in fact, a strategy that is harmful to their economies. This can be demonstrated by using, on the one hand, measures such as the balance of trade, the unemployment rate, wages or consumption levels. For example, consumption increases when migrants come to the country, and thanks to additional consumption, tax revenues grow, and so does the wealth of the society. On the other hand, the benefits can be presented most simply by comparing the level of contributions to the additional GDP of the 'old Union’ countries, which was generated by the accession of the 'new Union’ countries. In order to provide a fair justification for this, it would be best to compare the impact of the accession of the 'new Union’ (EU-13) countries on the socio-economic development of the 'old Union’ countries (EU-15). Such a high-profile analysis was published in June by Timo Baas in his work – The economic benefits of EU-13 membership. The results of this publication will be the basis for trying to answer the question of who has benefited more.

The effect of integration on trade

To estimate the economic impact of the EU-13 membership on the development of the EU-15 countries, the researchers used the computable general equilibrium model (CGE). Building a model makes it possible to create an alternative scenario that illustrates a non-existent world – in this case, it was the one in which the EU would still have the original 15 members. Then the obtained values were compared with the actual data. The difference between the scenarios reflects the impact of the accession of thirteen countries on the socio-economic development of the 'old Union’ countries.

However, it must be remembered that as with any method, this one also has its limitations, such as the static nature of the model, which does not take into account profits from foreign direct investment and trade resulting from stronger economic growth in the EU-13 countries. We know that these gains grow over time, so to some extent, the benefits of the EU-15 may be overlooked.

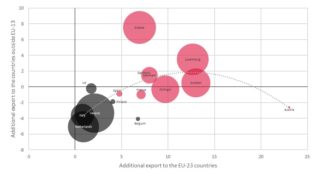

When analysing the additional benefits of the 'new Union’ membership in the EU-15 trade balance, it is clear that Austria (23%), Sweden (13%), Luxembourg (12.6%), Portugal (9.7%), and Denmark (8%) began to export significantly more to Central and Eastern Europe countries. The rest of the Old Continent (though to a lesser extent) also improved the level of exports of goods and services to the new EU members.

At the same time – which should not be surprising – the accession of the EU-13 countries triggered stronger competition in exports to countries outside the thirteen states. Here, too, we discover the EU-13 accession bonus for the countries mentioned. Western consumers benefit from lower prices due to increased imports. As a result, the inhabitants of the 'old Union’ could increase their prosperity faster than it would result from the normal pace of their development.

Chart 1. Additional exports recorded by the EU-15 due to the EU-13 membership (per cent)

Source: own study based on the publication by Tim Baas (2020)

Increasing prosperity in the West

Welfare can be interpreted as the higher utility (level of satisfaction with goods or services) of households.

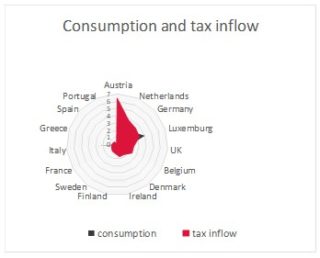

If not for the accession of new members to the EU, it would be lower by as much as 42.3% for the EU-15. As goods imported from the EU-13 are cheaper than domestically produced, households experience increased utility. As a consequence, in countries where we see a significant increase in imports, we also observe a sharp increase in consumption, which translates into the well-being of the inhabitants of Western Europe. On the other hand, the more people consume, the more the tax revenues grow that give governments the means to conduct public policies.

However, the UE-15 club is not uniform. The impact on additional tax revenues shows a clear difference in the countries of the 'old Union’ – in Northern Europe, they are higher than in the southern regions of the continent. It is indirectly related to the level of increase in additional consumption, which results from migration, among other things. It is worth emphasizing that two of all the countries of the 'old EU’ which gained the greatest additional tax revenues during the accession of the EU-13 are those of the “Frugal Four” – Austria (6.4%) and the Netherlands (3.8%).

Chart 2. Additional tax revenues, consumption and welfare in the EU-15 due to EU-13 membership (%)

Source: own study based on Tim Baas’s publication (2020)

Migration and changes in the labour market

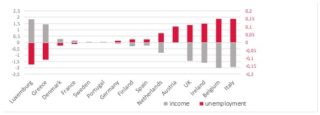

Also, the impact of EU-13 membership on the national labour markets of the 'old Union’ seems to deeply divide Europe. A clear relationship can be seen where the rise in wages is accompanied by a decrease in unemployment.

There is nothing unusual about this – wages are rising in those countries to which Europeans of the 'new Union’ decide to emigrate less often. This is especially noticeable in Luxembourg and Greece.

On the other hand, in countries such as Italy, Belgium and Ireland, the opposite effect can be observed, i.e. a decrease in the level of wages with – admittedly insignificant, but still – an increase in unemployment. In this case, it can be expected that Europeans migrating from the 'new Union’ will become competitors to their native inhabitants. Moreover, in countries with a high inflow of EU-13 citizens, wages in the EU-15 tend to decline as well. In this case, however, it is the migrants who themselves bear the costs of the fall in salaries, receiving less than the native inhabitants.

Chart 3. Additional wages, unemployment and prosperity in the EU-15 due to EU-13 membership (%)

Source: own study based on Tim Baas’s publication (2020)

Additional points to GDP

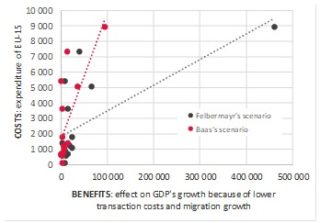

Opening to new members has also resulted in a greater economic development (measured by the GDP indicator) of all EU-15 countries. The combined impact is an additional 22.7% increase in GDP. Luxembourg has gained the most – 6.2%. The reason for such a high level is mainly the decline in transaction costs, which is particularly important in trade, transport and the financial sector. However, this is not the case all over Europe. Some countries have gained significantly less from the inclusion of new members into the Union. We are mainly talking about the economies of the southern part of the Community, which have not registered any additional GDP growth. The exception is Greece, whose GDP would have been 2% lower had it not been for the accession of the EU-13. How do the listed benefits compare to the amount of payments? Let’s see.

The north of the EU gains more

The volume of trade in services means that the differences between Baas’s scenario and Felbermayr’s scenario are large, as seen in the example of Luxembourg and, to a lesser extent, Finland. In Belgium, greater savings in import transaction costs harm domestic production and the export industry. Therefore, Belgium is the only country where GDP growth in Felbermayr’s scenario is significantly lower than in Baas’s.

Other countries, such as Germany, France, Austria and Sweden, benefit from a higher amount of transaction cost savings in Felbermayr’s scenario, which especially affects exports. Nevertheless, if we use the lower estimates from Baas’s scenario, the GDP growth for most countries still exceeds spending for the EU-13 countries. Only in the case of Italy and Ireland is the GDP growth too small to cover the costs, and in Spain and Portugal, they are very similar to GDP growth. This shows the unequal distribution of benefits between the North and the South of the 'old Union’. In other words, the economically stronger reap greater profits.

Chart 4. Costs and benefits of EU-13 membership on EU-15 GDP (million euro)

Source: own study based on Tim Baas’s publication (2020)

Union funds are not a part of redistribution policy

EU funds for Central and Eastern Europe are often seen by richer countries as a social programme or even charitable aid. This is not true. They should be treated as a policy of one’s own growth and a leading tool to stimulate one’s competitiveness and sustainable welfare. This is particularly important in relation to cohesion policy. The agreement of the last summit did not take into account any increase in funding.

We should remember that both nominally and in terms of the intensity of aid (i.e. euro per capita), the EU-13 countries will lose much more than the countries of the 'old EU’. The change in the allocation of funds under the cohesion policy after 2020 compared to the current MFF will mean a decrease by as much as 175% for the countries adopted since 2004, while the decrease for the EU-15 countries will reach 22%.

Moreover, this gap will not be covered by even EUR 390 billion in grants and EUR 360 billion in loans, which were supposed to amount to EUR 500 and EUR 250 billion, respectively, but their values were changed after pressure from Austria, Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland.

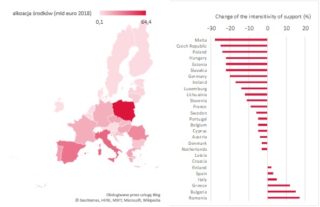

Chart 5. Change in aid intensity and the size of allocation of cohesion policy funds after 2020

Source: own study based on data from the European Commission

Did the winners lose?

Until now, debt sharing has usually been met with resistance from Eurosceptics. The agreement of the heads of EU governments should undoubtedly be treated as a symptom of deepening integration. The immediate impetus for this was not so much intentional action as the COVID-19 crisis. At present, we should be discussing the absorption of funds and their sensible spending rather than be engrossed in the discussion about the shape of the funds.

The Union has shown relative submission to the ‘Frugal Four’, which apparently is not entirely driven by clear motivations when viewed through the aspect of economic costs and benefits (additional GDP exceeds contributions) or when it comes to respecting the written and unwritten rules that guide the Multiannual Financial Framework. Therefore, one may be tempted to say that the ‘Frugal Four’ is not as big a winner as it might seem because without real solidarity no budget will serve the Union as a community.

However, looking back, it should be remembered that the winner of the enlargement of the Community (including Poland) is certainly the entire Union, especially if we look at total economic benefits. It is worthwhile to pump more funds into the EU, despite the opposition of the ‘Frugal Four’.

According to forecasts, each euro invested in the period 2007-2014 will increase GDP by EUR 2.74 by 2023. In the same period, 570 thousand jobs were created, 160 thousand of that in the new Member States, and nearly 200,000 of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) received direct investment aid. These are benefits that may not be repeated without sufficiently high contributions. The aggressive rhetoric of the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden is wrong – we all benefit from European integration and from ever larger EU budgets.

Polish version is available here.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" (below) is mentioned.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" (below) is mentioned.

The publication co-financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland as part of the public project "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" („Dyplomacja Publiczna 2020 – nowy wymiar”). This publication reflects the views of the author and is not an official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.