The War over 5G: A New Hope for Transatlantic Cooperation

W skrócie

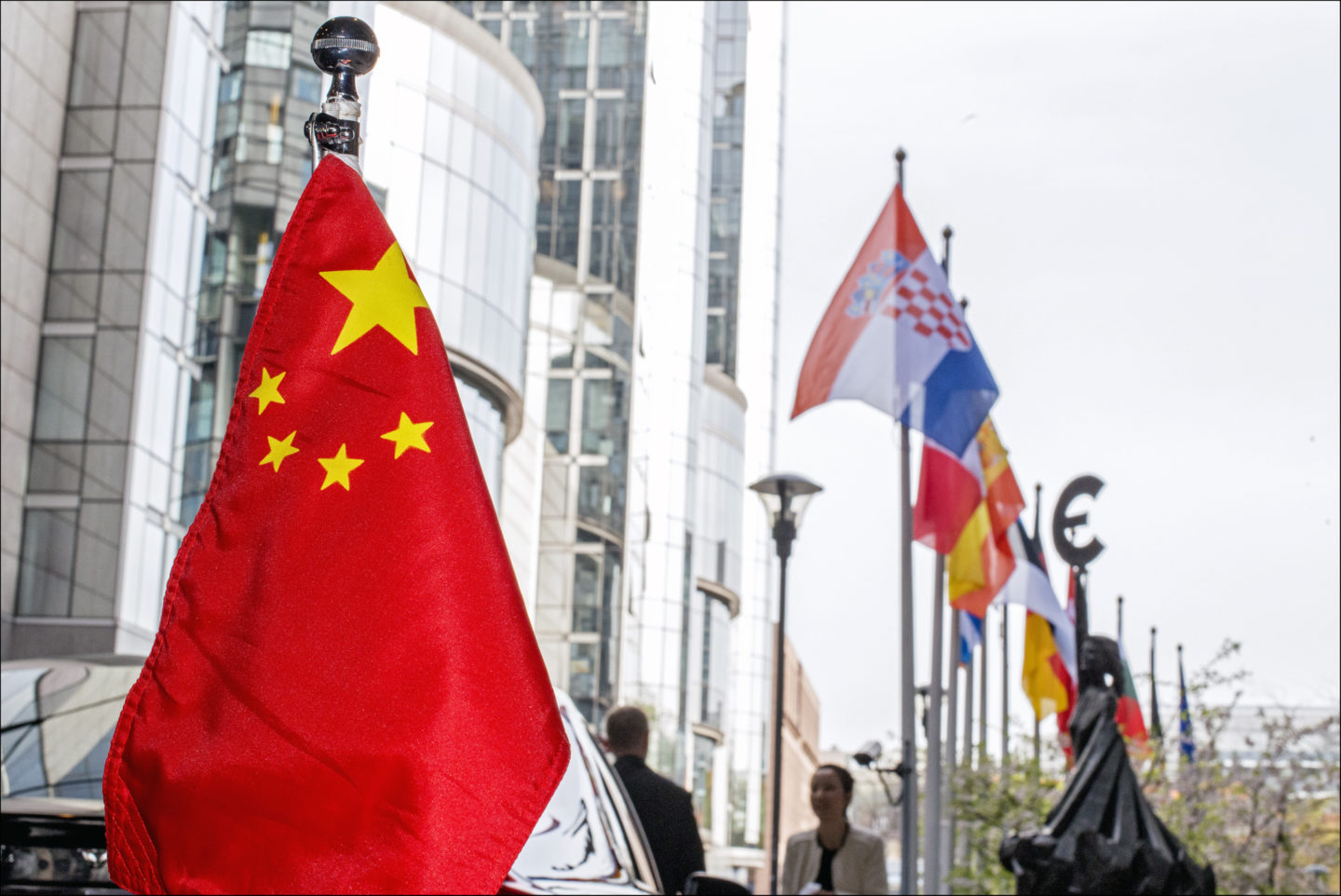

Any exacerbation of US–China relations puts pressure on the EU to clearly stand on either side of the barricade. While relations between Washington and European partners have become increasingly tense during Donald Trump’s presidency, the US–Chinese technological rivalry offers an opportunity to renew European–American cooperation.

Competition landscape

In recent years, we have witnessed increasingly escalating tensions. Critical statements by politicians and the actions of the administration of both powers led to the trade war, for example, which is far from over, even if it’s been temporarily silenced. The dispute also transfers over into the dimension of the latest technologies.

American pressure to discourage EU countries from adopting Chinese 5G technology, and the US Department of Commerce placing the Chinese giant Huawei on the blacklist of operators which American corporations cannot cooperate with, show that the list of conflicts between Beijing and Washington is ever growing. Add to this the dispute over democratic values and human rights—which is appearing in public discourse more and more—and the Hong Kong events, and the picture of an American–Chinese rivalry starts to look extremely complex. At the same time, there is the issue of how the community of EU countries should react to further actions by the US and China.

The traditional commitment to global American politics, forged during the Cold War, is often questioned. Doubts especially arise when further tariffs are imposed on EU–US trade, and statements by both Trump and some European politicians strain relations.

According to the Poland–Germany barometer from 2019, only 15% of Germans express positive feelings towards President Trump. This is a worse result than that obtained by… Vladimir Putin, who received 29% positive opinions. Seeing such data, one may start to wonder if Emmanuel Macron’s words about NATO’s 'brain death’ apply to the whole transatlantic relations.

Cold War comparisons are wrong

As always, such bold statements should be taken with a considerable dose of scepticism. We must certainly realise that—contrary to popular opinion—the current rivalry between powers in no way resembles the Cold War.

In contrast, China does not threaten the whole world militarily, and certainly not Europe, which is the first crucial discrepancy between this situation and the 20th century. Back then, the fear of the Warsaw Pact troops actually fostered stronger transatlantic ties.

The second difference is commerce. In the global trade in goods and services, China has reached a level that the USSR never even came close to. Consequently, imposing tariffs or sanctions on Beijing will hit the world economy much harder than similar actions against Moscow during the Cold War. While the US–Chinese trade war brought some profit to the US (at least in the short term), it may generate serious losses for some EU countries (including Germany). During the Cold War, the united front of Western Europe and the United States was more natural than today’s unanimity with regard to the PRC.

As more American troops are withdrawn, the legitimacy of NATO’s defence of its smaller members is being questioned, and in the face of many other minor clashes, one must ask whether there is anything that would allow for a ‘new opening’ and deepening of EU–US relations. It seems that we can expect such an opportunity and positive action in the area of development and implementation of the latest technologies.

China’s expansion in the digital world

China officially launched its offensive in new technologies when Xi Jinping announced in 2017 that the PRC would become comprehensively modernised by 2035. The Chinese IT industry is to play a key role in achieving this goal. The purpose of the implementation is Made In China 2025 (MIC2025), a project which sets out China’s strategic agenda, presented by Prime Minister Li Keqiang in 2015.

The main assumption of the programme is the economic transformation of the country from manufacturing mainly cheap, low-quality goods to more advanced equipment and modern technologies, in order to gain independence from foreign companies and to change the production profile in China. Beijing announced that once the plan has been implemented, the latest solutions in particularly important development areas—such as logistics, transport, health care or industry—will be provided by domestic manufacturers. The plan also has adequate funding, as we are talking about a total of up to 300 billion USD for the implementation of MIC2025.

Meanwhile, the Chinese are investing, for example, in European companies in the sectors that are listed in MIC2025, in order to keep up-to-date with European know-how by holding shares in them and using often controversial means (e.g. industrial espionage). Currently, the export of 5G and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which Beijing is trying to take advantage of, is particularly security-sensitive whilst offering significant benefits.

At the same time, despite concerns, EU countries still work with Chinese companies, at least partially. This is due to the fact that the community has been lagging behind in the development of 5G and AI technologies for a relatively long time.

Publications of the Kosciuszko Institute – The future of 5G, or quo vadis, Europe? and 5G: Opportunities, threats, challenges – show that whilst many of the reported 5G patent ‘families’ were created by European companies (Nokia and Ericsson), the amount of investment in research and development of this technology remains relatively low. Though the 2018 financial expenditure of the two leading European manufacturers amounted to 3–5 billion EUR, Huawei spent over 13 billion EUR.

In terms of AI, according to data presented by the Centre for Data Innovation in the article entitled Who is winning the AI Race: China, the EU, or the United States?, in 2017–18, the US spent around 16.9 billion USD, China spent 13.5 billion USD, and the EU allocated only 2.8 billion USD for this purpose. Of course, the European Union still has enormous potential in the field of innovation, a large group of scientists, and many acquired start-ups, so the hurdles can be overcome, with greater involvement of appropriate financial expenditure.

Partnership and systemic competition

It would seem that the EU as a community of states may soon join the global rivalry in support of the US. It should be noted that for other countries in the world, and more specifically for their citizens, the threat related to the development of new technologies means not only possible interference from China, but also the risk of using digital gains against inhabitants. This, in turn, increases the competitiveness of the European offer, an important point part of which is the defence of human rights.

In EU–China: A strategic outlook, a report published in 2019 by the European Commission, the following sentence can be found on the front page: ‘China is, simultaneously, in different policy areas, a cooperation partner, an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.’ This passage seems to aptly capture the appropriate starting point for creating a European stance on the rise of China’s power and the US defending its position.

Trade and cooperation with Beijing are desired by the EU, but at the same time there are fundamental divergences that focus, e.g. around the approach to democratic values and respect for human rights. The sphere of technology highlights those areas quite clearly.

The advancement of digitisation will provide governments with a risky opportunity to use it to build modern systems of surveillance and repression. This is one of the main themes in the report from the Centre for Strategic & International Studies, The US–China Race and the Fate of Transatlantic Relations by Andreas Ortega. He points out that both the autocratic China and the US will seek to promote their approach to using technology, particularly in the AI sector. The report postulates that the EU and the US should join forces as soon as possible to create a common digital agenda that would be able to convince the world to implement new technologies while respecting the freedom of citizens. They should do so if they seriously want to build their global position as promoters of a democratic order.

EU response

In 2017, Xi Jinping started the process of forging a Chinese model of legal solutions for the use of new technologies. One example would be the Chinese Four Principles of the Global Transformation of the Internet Management System, which is rich in brilliant generalities—such as respect for digital sovereignty—but put emphasis on the state and ignore the rights of citizens. The purpose of unclear rules is primarily to encourage third-party countries to buy technology from Beijing, which in return will not expect respect for human rights and democratic values that might impact the transfer of technology.

What could counter China’s offer? The European–American proposal will have to be available and of the highest possible quality, must be based on the suppliers’ credibility, and must offer regulatory proposals that define the way the technology is to be used. The EU can meet all these conditions. Nokia’s latest achievement is a cause for optimism, as in May of this year they set the world speed record for 5G technology. EU technology can therefore compete in terms of quality. What of the other components of what we can offer?

Regulations concerning the implementation and use of new technologies can be a useful tool for EU countries, but also for others that decide to get them from China. Appropriate regulations allow state institutions to reduce the risk of unwanted use of 5G and AI by the authorities in Beijing and to reassure their citizens that the state would not use these novelties against them. Importantly, in the reality of the global economic crisis, creating a new law will be cheaper than a sharp increase in spending on high technology, and may also bring significant results. Some guidance on how this should be done in practice can be found in the ongoing efforts of EU governments to introduce 5G.

A good step seems to be obliging the member states to exchange information, jointly scan public procurement contracts concerning new technologies, and detect threats (backdoors) that might be used, for example, by China or another supplier from outside the EU. It is worth making such commitments binding on EU members and implementing them within the existing European Network and Information Security Agency. Furthermore, the Member States themselves should always take care to ensure that adequate national legislation is in place that would give countries the tools to oversee new technologies and promptly deal with security incidents.

Perhaps we will be able to dispel many ambiguities regarding the shape of EU regulations during the current German presidency of the EU Council, whose agenda—like the current European Commission—will most likely include carrying out the digital transformation in parallel with the Green Deal.

Technological bridge of understanding

The core values that characterise the societies of the West are common to all its members, but despite this, there are discussions between them regarding the use of technological advances. This is clearly illustrated by the approach to online privacy or the right to be forgotten, which significantly differentiates the EU from the US. Disputes regarding this issue have arisen more than once and will keep recurring, stirring up public opinion, but this does not necessarily rule out cooperation.

This thesis is confirmed by recent events. Apple’s and Google’s solution for contact tracing, recently described on the website of the Jagiellonian Club by Bartosz Paszcza, shows that Big Tech from the US are able to guarantee the privacy of users as required and expected by the EU. We should demand cooperation between Europe and the US-based IT industry and demand similar openness from the Americans. Only when this technology is developed in both regions will we be able to successfully compete with Chinese suppliers on a global scale.

Moreover, there is a need for a broad discussion on how to use ever newer technological solutions. Unlike the commercial sphere, modernisation puts both sides of the Atlantic firmly in the same position vis-à-vis China, even if we have different approaches towards taxing digital giants or, for example, protecting personal data and privacy when using new technologies. However, the desire to secure common values may give new dynamics to the transatlantic relationship, whose wheels seemed to grind more often recently. The new agenda promoting the democratic use of the latest technologies has the potential to show the rest of the world a proposal that will bring them into our sphere of influence.

It is worth believing (as does Andreas Ortega, quoted above) that the search for a common model for managing new technologies based on shared values will allow the countries of Europe and the US to understand and rearticulate their strategic goals in the changing world of technology and beyond.

Polish version is available here.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" (below) is mentioned.

Publication (excluding figures and illustrations) is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Any use of the work is allowed, provided that the licensing information, about rights holders and about the contest "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" (below) is mentioned.

The publication co-financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland as part of the public project "Public Diplomacy 2020 – new dimension" („Dyplomacja Publiczna 2020 – nowy wymiar”). This publication reflects the views of the author and is not an official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.